Pomar Square and the Limits of Public Space

Designed as part of Lucio Costa’s 1960 master plan for Barra da Tijuca, in Rio, Pomar Square is a rectangular park at the center of a radial plan of streets, set in what is today a dense residential area. The fabric of low-rise buildings that surrounds the Square creates a figured public space, not unlike many pre-modern plazas in European cities such as the Piazza Navona, in Rome, or the Puerta del Sol, in Madrid. [Image 01] However, contrasting with these, Pomar Square is a green island created by busy car lanes, a fenced perimeter, and is accessed only through four controlled gates - one on each corner. The monumentality evident in a plan or aerial view is deceptive. Not only is the park geographically and spatially isolated but it is, for all practical purposes, closed. [Image 02]

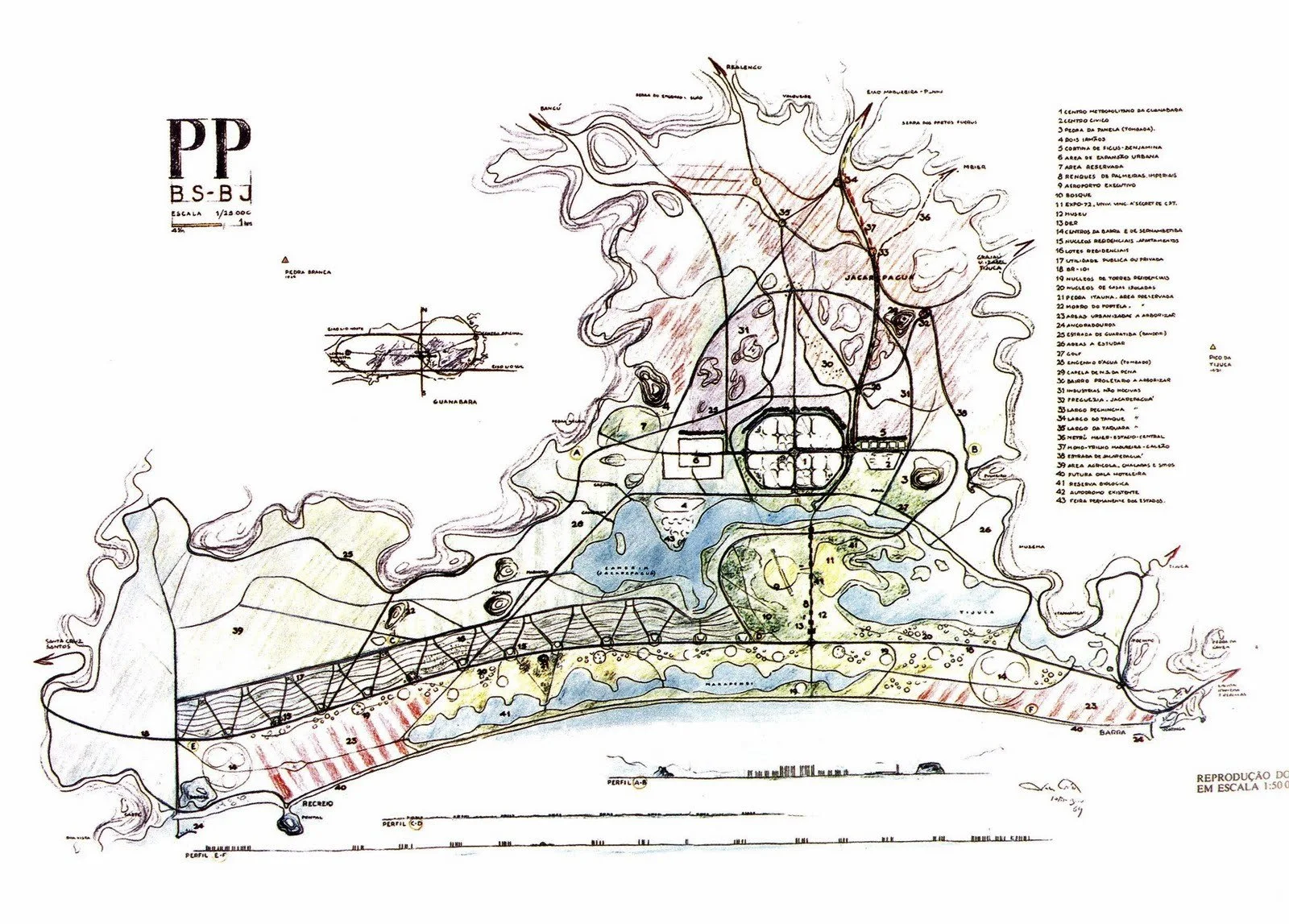

Barra da Tijuca Masterplan, 1969

Source: COSTA, Lucio. Plano Piloto para a urbanização da baixada compreendida entre Barra da Tijuca, o Pontal de Sernambetiba e Jacarepaguá. Arquitextos, São Paulo, ano 10, n. 116.00, Vitruvius, jan. 2010

Aerial view of Pomar Square, 2020

Source: Sebastiao Zimmerman

To understand the situation of the Square, one must first examine the coastal public spaces in Rio de Janeiro. A city sprawled along a vast beachfront, between sea and mountains, Rio has contrasting neighborhoods: on one side, the extensive unplanned and informal settlements to the North, and the orthogonal grids of postwar modernist urbanism of upper-income neighborhoods along the shore. In this context, Pomar Square can be analyzed as a proxy for the eight other public squares within walking distance from the beach in privileged neighborhoods such as Barra da Tijuca, including Leblon, Ipanema, and Copacabana. Due to the hot weather and few explicit restrictions on behavior at the beach, the sandy expanse ends up being the main destination for residents during their leisure time. It is an almost infinite public space with easy access by multiple forms of transportation and, just as important, with little to no surveillance. In effect, even nearby small urban parks have little draw. [Image 03]

Central water fountain without use, 2022

Source: Unknown

In planning terms, Pomar Square is a paradox between design and site. On the one hand, the design is limited by the deterministic tendencies of modernism (and their classical models), and, on the other, it suffers from underuse due to its location – physically and socially. In simple terms, the Square has been abandoned. Formally, it offers an illusion of civic control but, in the neighborhood, it is considered unsafe and home to any number of anti-social behaviors and vandalism. Not long ago, residents put up a sign that said “Be careful, constant robberies in this area.” [Image 04] Apart from the fences, signs on all the entrances list rules and expected behavior during opening hours (7am to 6pm) – ball games, barbecues, dogs, and commercial activities are not allowed. Visitors can also find a sign with numbers of emergency contacts and are recommended to report any “misbehavior”. [Image 05]

The relationship between pedestrians and vehicles is also of special interest in this case study. Pomar can be seen as a “lost space” - as are many of its peers in the area: a public space “in need of redesign, antispaces, making no positive contribution to the surroundings or users” Writers variously blame cars and the privatization of public spaces for shaping this condition; others see “neglected” spaces, “invaded” spaces, and “exclusionary” or “under-managed” spaces. All are symptomatic of deep problems in maintaining public space.

Sign put up by residents: “Watch out: constant robberies in the area”, 2014

Source: O GLOBO Rio

Sign of rules and opening hours, 2020

Source: TripAdvisor, Joffran Tavares

Barra da Tijuca was planned as a car focused neighborhood, being built during the 60s, soon after Costa's Brasilia (with many buildings by Niemeyer). Even though the zone where Pomar Square is located - Jardim Oceanico - is one of the most walkable areas within Barra, cars are still the protagonists. Zoning policy reduced commercial activities to a few streets, and residential buildings with fences or walls, and several car lanes created unpleasant pedestrian spaces. Together, the scenario set the ground for a constant feeling of risk among residents, which resulted in extremely reduced pedestrian traffic and consequently, a further withdrawal from public spaces. [Image 06]

Pomar Square is under the jurisdiction of Rio's Parks and Gardens Department and is cleaned by COMLURB, the Municipal Urban Cleaning Company, but it is not only an under-utilized gem of upscale Jardim Oceanico, it is woefully under-funded. Situating this within the larger context of Brazil, and more specifically, of Rio de Janeiro, we must take into account the legacies and impact of mega-events in the city, and the national political turntable and impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016. After the peak of global investments between 2007 and 2016, largely in Barra da Tijuca - the main hub for the 2016 Olympic Games - the scenario that followed was one of a “large financial crisis in sub-national state governments.” Rio suffered from global economic trends, including a drop in oil prices, and thus reduced tax revenues, as well as questionable tax exemptions at large corporations involved in public-private partnerships in large urban projects. Between 2016 and 2021, Parks and Gardens’ annual budget was cut by 58%, leading to the need for concerned citizens and neighborhood groups to search for other forms of funding to maintain even minimal conditions. [Image 07]

Pedestrian space withdrawal, 2022

Source: Google Street View

Cleaning by COMLURB, 2020

Source: Prefeitura Rio Website

In 2018, the city of Rio passed a law that allowed the "adoption of public spaces'' (ADOTE.Rio), where organizations, firms, or individuals could "purchase" a part of a park or its entirety in exchange for marketing space at signs, recognition in official websites, social media marketing, and so on. The department’s director Cristina Monteiro claims that the program is “part of a global movement,” where public entities “are unable to care for public spaces due to lack of funding.” ADOTE followed the examples of Porto Alegre and São Paulo, in Brazil, as well as cities in the UK and in the US (privately owned public spaces or POPS, starting in the early 1960s, and Business Improvement Districts or BIDS, starting in the 1970s).) where “shrinking local government transfers power for the management of public spaces from the state to private businesses and organizations or individuals.” Since then, over 1.5 million square meters of public spaces including plazas, gardens, monuments, and even trees have been adopted. Pomar Square is still available.

Differently from its American and British counterparts, ADOTE forbids any kind of commercial exploitation in public spaces, being the sponsor - or as they call it “adopted parent” - strictly in charge of maintenance. However, since the first version of the program, rules have been softening and business owners are adopting spaces in front of their shops to remove the homeless that often sleep in urban parks - excluding undesirable populations and prioritizing security concerns over social interactions. Recently, former secretary of Healthy Aging, Life Quality, and Events in Rio, Felipe Michel said he intends to allow for commercial activities in adopted spaces. This commodification of services means that “needs formerly met by public agencies are now met by companies selling services.” Public space is increasingly branded, and ADOTE’s policy of benefits is only one of many recently implemented systems following this trend. [Image 08]

ADOTE.Rio, 2022

Source: ADOTE.Rio’s website

The current status of Pomar demonstrates state disinvestment in urban infrastructures, including parks. The park's facilities have not been maintained in years, and are permanently closed. The few walls and buildings within the plaza are constant targets of vandalism and trash accumulation, and homelessness in the area has increased. Public employees of COMLURB are often seen cleaning and washing the surfaces. Recently, a new surveillance system was implemented, with police officers driving around in cars and vans, or on bikes, or merely on foot. Their schedule (day and night) and expense reports were made public by the organization. Yet, urban observers have found that surveillance can “increase the perception of safety, [but] it can also contribute to accentuating fear by increasing distrust among users.'' In addition, consistently prioritizing security over social interactions destroys the democratic expression of publicness. In other words, the park has not been privatized, and the state uses law enforcement to do the minimum for public safety.

Looking for an alternative solution – as set out by ADOTE – residents of the surrounding streets (mostly the elderly) held fundraisers to support the square, and their association (Amar) is often in dialogue with City Hall and the Parks and Gardens Foundation to report any misbehavior, need for specific cleaning and/or maintenance. In this way, Pomar demonstrates that neither private nor state-owned entities are the answer for sustainable common resources. Instead, local, self-organized forms of governing need to drive wise management of public spaces. Pomar is an example where individuals (slowly) take over maintenance and surveillance to avoid the decay of the neighborhood they live in but it is not enough. Through “commoning” – a politics of sharing – indigenous cultures or local cooperatives can claim or set design principles to secure responsible governance: “clearly defined resources and users, congruence between appropriation, provision rules, and local conditions.” The residents and businesses around Pomar, in tandem with the City and its Parks department, need to organize and take further the maintenance and care of the park as social infrastructure and as localized public space that, in turn, can contribute to the City’s daily life.

Bibliography

Roger Trancik, Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design (NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1986).

David Engwicht, Street Reclaiming: Creating Livable Streets and Vibrant Communities (New Society Publishers, 1999).

Matthew Carmona, "Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification," Journal of Urban Design 15: 1 (February 2010) 123–148.

Chat Travieso, "A Nation of Walls: The Overlooked History of Race Barriers in the United States," Places Journal, September 2020.

Raewyn Connell, "Understanding Neoliberalism," in Susan Braedley and Meg Luxton, eds., Neoliberalism and Everyday Life (2010) 22-36.

Jeremy Németh, "Defining a Public: The Management of Privately Owned Public Space," Urban Studies 46: 11 (October 2009) 2463–2490.

Karin Bradley, "Open-Source Urbanism: Creating, Multiplying and Managing Urban Commons," Footprint 9: 1 (Spring, 2015) 91-108.

Fabricio Leal de Oliveira, Carlos B. Vainer, Gilmar Mascarenhas, Glauco Bienestein, and Einar Braathen, “Mega-events, legacies and impacts: notes on 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics” (2019)

Kilian, T. (1998) Public and private, power and space, in: A. Light & J. M. Smith (Eds) Philosophy and

Geography II: The Production of Public Space, pp. 115–134 (Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield).

https://www.rio.rj.gov.br/web/transparencia/execucao-da-receita-e-da-despesa

https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/prefeitura-anuncia-regras-para-adocao-de-bens-publicos-23392380

https://diariodoporto.com.br/pracas-publicas-do-centro-podem-ser-adotadas-por-empresas/

https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/sem-manutencao-passeio-publico-mostra-sinais-de-abandono-23644095